The National Park Service Wants to Rename Beaver Valley to Woodlawn

Three reasons we can't let this happen.

Dec 9, 2019

Photo by John Crossan

We have some very disturbing news. The local National Park Service office who oversees the First State National Historical Park began taking steps to rename the park from "Beaver Valley" to "Woodlawn". They'll be changing the name everywhere from within the park's Foundation Document and all future communication even down to their interpretive signs. This strange turn of events is like something out of an M. Night Shyamalan movie. As many of our followers may remember, we actively fought Woodlawn for years from turning their open space into dense housing developments and commercial shopping centers. The decision to rename the land from "Beaver Valley" to "Woodlawn" is culturally insensitive and distructive to Beaver Valley's history.

If you’d like to stop Woodlawn’s name from forever branding a valley that we fought for five years to preserve, then you’re not powerless.

Here are the top three reasons to keep Beaver Valley's name:

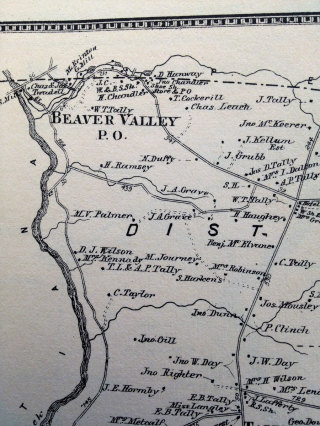

1. This land has always been known as Beaver Valley

Old map referring to the region as Beaver Valley.

Pomeroy and Beers Atlas of the State of Delaware.

http://data.dgs.udel.edu/sites/1868hundreds/pdf/brandy.pdf

Photo by John Crossan

Before the settlement by Europeans, Beaver Valley Cave was used for rest, shelter and storage by the Lenni Lenape. In the late 17th and 18th centuries, the land was taken up by Europeans, many Quakers, many coming with William Penn. The first reference to Beaver Valley was in 1694. The lands were cleared, surveyed, and domesticated into the dispersed family farms that characterized classic settlement patterns in the area. Beaver Run and its tributaries supported small mills that produced lumber, tin, flax and paper. Road Orders from both the State of Delaware and from Chester County PA confirm that Beaver Valley Road in DE was laid out in 1751, and Beaver Valley in PA was laid out in 1772.The U.S. Postal Service officially designated the area as "Beaver Valley" in 1865 when a Post Office was established in the village, A major reason for the creation of the First State National Historical Park was to explain and honor the history of the area. Changing the name of this unit of the park from Beaver Valley to Woodlawn undermines the Park’s purpose.

2. Today, the name Beaver Valley is at the center of our community

Hikers in Beaver Valley.

Photo by Joe Del Tufo

Beaver Valley is not only a part of our history and heritage, but it is also an integral part of who we are today. Generations of people in the area know this land as Beaver Valley. People of all ages commonly refer to Beaver Valley as the place for hiking, biking, horse riding, bird watching and overall scenic beauty. Bumper stickers and t-shirts can be seen everywhere proclaiming "Save the Valley." Just as one wouldn’t abide renaming Brandywine Valley or Delaware Valley, we should not consider renaming this section of the park for the former owner of the land, especially one who blatantly ignored the historical, cultural, environmental and recreational value of the adjacent land when seeking to bulldoze it for profit. Keeping the name Beaver Valley for this section of the park more aptly describes the land, its current relevance, and the principles of a national park.

3. Woodlawn doesn’t deserve to have its name associated with a national park

Vernon Green, Woodlawn's spokesman speaking at a public meeting about developing 270 acres in Beaver Valley. In the background, the community actively opposing Woodlawn's actions.

Renaming the “Beaver Valley” unit of the First State National Historical Park to “Woodlawn” is to give it the name of an organization that has betrayed William Bancroft’s mission repeatedly over the past several decades. Bancroft originally charged the Trustees more than a century ago with “gathering up the rough land north of Wilmington and holding it for future generations” and to also use the rental income from the 450 apartments and houses he built in Wilmington (“The Flats”) to preserve more land. Yet time and time again, Woodlawn has sold off large parcels to build shopping centers and housing developments.

In 2012, after selling 1,100 acres to Mt. Cuba and the Conservation Fund for $21 million (but then characterizing their sale as a donation), Woodlawn pawned off to an affiliate board member 325 of its acres adjoining what would become the First State National Historical Park. Not only was all of this land receiving tax subsidies under a Pennsylvania preservation program called “Clean and Green,” but at least two different families sold their large estates to Woodlawn because they were led to believe it would be preserved.

It took substantial legal sums through the Beaver Valley Conservancy to defeat these development plans in court, and the final cost to buy the land from the equitable owners was likely three times higher than Woodlawn’s wholesale price to the developer. Woodlawn would, of course, claim that it’s liquidating Bancroft’s legacy because it needs to fund its housing operations in Wilmington, but that ignores two inconvenient details. The first is that The Flats in Wilmington generate upwards of $4 million in rents each year. And, second, Woodlawn could have sold their land to a preservation organization instead of a developer sitting on one of their affiliate organizations.

Woodlawn betrayed William Bancroft’s mission in other ways, too. As a Quaker, Bancroft was enlightened beyond his time, so he would have been rightly appalled by the lawsuit filed in the 1970s against Woodlawn by the federal government for racial housing discrimination. He would no doubt have been ashamed by Woodlawn’s shedding of their nonprofit status in the late 60s after the IRS investigated them for being undeserving of 501(c)(3) nonprofit status. Everyone who’s lived in the area around Beaver Valley has known for decades that Woodlawn has really become a developer, headfaking everyone with their “conservation mission” as they have slowly liquidated their land for the benefit of politically connected people in Wilmington.

Despite this history being well known among residents of two states, Woodlawn continues to signal they will not stop selling off land for development. Woodlawn still owns roughly 350 acres surrounding the National Historical Park, yet they continue to ignore calls to sell those remaining acres to a preservation consortium.

In the end, it’s been quite a shock for those of us who know Woodlawn’s history and who’ve witnessed first hand Woodlawn’s unsavory practices to learn that a unit of the First State National Historical Park would bear their name. It’s an outrageous proposition to the hundreds of thousands of Brandywine Valley residents – who know the land only as “Beaver Valley” – to rename this beloved place after a reviled organization.

Ready to do something about it?

Take action! Don’t just sit there and shake your head ruefully as you watch a historic piece of our history wither and die, do something about it. We feel that the best way to have an impact is to pick up the phone and call the National Park Service and Delaware state Senator Tom Carper's office. We understand phone calls are a little more difficult to make and take some courage to do, but we think you're well-equipped for the task! We recommend calling both the local and the regional offices. When you're done calling, please let us know that you did by filling out the form below. Here's how.

Take Action

Pick your favorite reason to keep the name of Beaver Valley. Or maybe you have more than one.

- Historically, the land has always been known as Beaver Valley.

- Everyone today already knows the land as Beaver Valley.

- As the party attempting to destroy Beaver Valley, the name Woodlawn doesn't deserve to be associated with the national park.

Now get calling! Take one minute per call. You may reach a live person who will transcribe your message to be delivered to the recipient. You may also get a voicemail. Be prepared for either. How big of an impact will you make? Will you call all four?

- Your first call is Acting Superintentant of the First State National Historical Park, Eric Breitkreutz. (617) 794-1986 If inbox is full, try the park's main number: (302) 544-6363

- Next, call the Regional Community Planner of the NPS, Sarah Killinger. (215) 597-2159

- Now we'll move to Senator Carper's office in Dover. Call Larry Windley, Senior Director of Projects & Economic Development. You'll have to call the main Dover office at (302) 674-3308 and ask for Larry Windley.

- For this last one you'll be calling Senator Carper's office in DC. You'll be calling Elizabeth Mabry, U.S. Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works at (202) 224-8832. They'll ask for your name before putting you through.

Let us know how your calls went!

Donate

Save The Valley is funded exclusively by donations from people like you. Articles like these are critical in keeping the public informed about important issues relating to Beaver Valley but require donations to keep them going. If you find this article valuable, please consider making a donation today. No amount is too small. Your donations are a critical part of keeping this effort going. Please donate today!

If You Found This Article Useful...

Save The Valley is funded exclusively by donations from people like you. Articles like these are critical in keeping the public informed about important issues relating to Beaver Valley but require donations to keep them going. If you find this article valuable, please consider making a donation today. No amount is too small. Your donations are a critical part of keeping this effort going. Please donate today!