An Overview to A Complicated Story

This is a big, complicated issue with a long history. There’s no getting around that. It’s important, however, that our supporters understand the whole story because what’s going on in Beaver Valley is anything but typical land dealing that involves typical development proposals.

Just What is The Valley, Exactly?

Let’s do a little time-tripping for proper context now. William Poole Bancroft was born in Wilmington in 1835. His father, Joseph, started a milling company, Bancroft Mills, along the Brandywine Creek in northern Delaware, and by 1930 or so it was one of the largest cotton-finishing operations in the world. From his experience working at the mills, William learned to value the natural beauty of the area and, having become increasingly troubled by the growth of Wilmington, began to fear that the future would see the city eventually merging with Philadelphia, leaving no open or green space in between.

Thus, Bancroft began purchasing as much land as he was able in the Brandywine Valley, with the intention that it be preserved in perpetuity as an unspoiled recreational area. Eventually, William held more than 1,300 acres and, after realizing that such parklands should remain intact after his death — or even be improved upon — he formed the Woodlawn Trustees “for the benefit of the people of Wilmington and its vicinity.” That organization’s original purpose was “to acquire [land] without limitation as to amount, by gift, devise, purchase or otherwise.” Much of this land has eventually become both state and federally owned parkland... yet much of it has been developed as well — contrary to William’s original vision and objective.

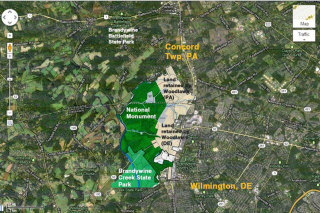

Flash forward to the present: Even casual observation en route between these two cities reveals that Mr. Bancroft was not terribly far off in his concern. It’s true that what’s now between Wilmington and Philadelphia is, for the most part, a mass of development and sprawl. There are many parks and areas of preservation along the way, but the majority of this corridor leaves little doubt that it lies well within the larger “megalopolis” between Washington, D.C. and Boston. Interestingly, and as a fairly stark contrast, one need not travel too far west to find large swaths of land that remain mostly untouched by modern-day expansion. Beaver Valley serves as a prime example: Though it is quite firmly in the midst of typical rampant development and population growth, it has much more in common with truly rural areas that lie dozens or even hundreds of miles farther inland, away from the East Coast. Recognizing both the Valley’s proximity to that sprawl and the fact that it’s an easy target for future expansion, our movement was started by two separate organizations, Save The Valley and The Beaver Valley Conservancy (BVC), with a common goal: to save Beaver Valley from development.

An Unmatched Habitat

The northern edge of one belt of permanently preserved and protected land combines with another adjacent section of privately owned and permanently protected space. Nestled within is a small area where most individual landowners use their acreage consistently with good conservation and preservation practices. The whole of Beaver Valley, including the Woodlawn land that’s been proposed for development, provides a nearly unmatched habitat for Mid-Atlantic Piedmont flora and fauna. Along with the stone and frame 18th- and 19th-century dwellings and outbuildings that dot the landscape — barns, corn cribs, cart sheds, and springhouses — the area provides a true evocation of our regional rural heritage. Crisscrossed with miles of trails, the Valley offers a magnificent recreational haven for bikers, hikers, and horseback riders.

The importance of this area has been recognized by New Castle County, which has recommended that the Delaware roadways winding through it be designated as national scenic highways; by the Delaware County Planning Commissions, which have encouraged its preservation and protection; and by the United States, which designated a portion of it as First State National Monument in early 2013 and more recently changed that designation to First State National Park. The haunting and magical character of this land was effectively captured by the National Geographic Society in March, 2013, when it described it as existing “at some indeterminate point in time…somewhere between the 18th and the 20th centuries.”

So Which Parts are Now Protected And Which Parts are Threatened?

Slightly more than half of the Valley’s lands are included within that newly designated First State National Park, and are thus permanently protected. Another 15% or so is held by individuals and operated as farms or country places. Some of these privately owned properties are also permanently protected with conservation easements; others are expected to be so protected in the near future. The remaining acreage is owned by Woodlawn Trustees, Incorporated, a Delaware corporation: Approximately 60% of that lies in New Castle County, Delaware and 40% is within Concord Township, Pennsylvania. All adjoin the First State National Park and Brandywine Creek State Park.

A History of Selling Out?

No one should be fooled by their name — the Woodlawn Trustees are not stewards of the land, as the organization was originally conceived. This group is now a development company much like any other. Instead of selling their acreage to a consortium of preservation concerns, as the name might imply, the Woodlawn Trustees have sold to other development companies who’ve made numerous attempts to change zoning laws. These developers have not been happy with what they can build legally, and rather than operate within that framework they’ve tried to get building regulations modified to better suit their agendas. As a result, thousands of citizens have united in an attempt to defend and protect this land that remains so meaningful to the surrounding communities. This is a large part of what led to the formation of both the BVC and Save the Valley, simply because — where expansion and development are concerned — some local jurisdictions have fallen short of enforcing their own rules.

Building Past Capacity Should Not Become a Norm

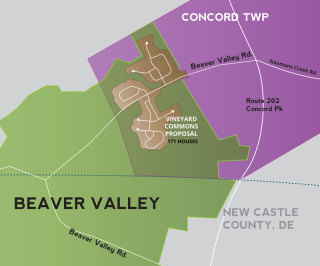

It is unclear exactly when Woodlawn decided to monetize its country properties by developing them. It is not even known how much land they really own or have owned in the past; they are not required to disclose such information. Regardless, the fragile ecosystem, historic treasure trove, and huge recreational asset that is The Valley is thus threatened. Although many urged Woodlawn to do otherwise, one of its more-recent plans was to sell its 321-acre parcel located in Concord Township to other developers instead of offering it to those who would protect it or work with local organizations toward that end.

This proposal, known as the Vineyard Commons, became a perfect example of attempts at changing the rules. Laws prevailing at the time allowed only a fraction of the development that was planned. So the developers submitted a “rezoning proposal” to accommodate their projected development. In other words, they put forth a request to change the laws to allow for an enormous increase in development so they could maximize their profits. Originally proposed were three large residential developments that would see 550 new homes built, along with a massive quarter-million square foot commercial complex that would have included a nationally opposed big-box retail store. The decision makers in charge of either accepting or rejecting such proposals are the five members on the Concord Township board of supervisors.

Beating The Rezoning Idea

Through an enormous effort, Save the Valley was able to rally almost a thousand people to the Board of Supervisors meeting in May of 2013 to oppose the rezoning proposal. After such an uproar, the developers were forced to withdraw their plans to rezone, having recognized that their initial ideas for Vineyard Commons would not be accepted by the community at large. Part of the public’s reluctance to allow such invasive development was the sheer number of homes planned and the housing density that would result. Other factors that became clear later concerned the lay of the land itself (construction on and amid so many steep hills is simply impractical), the increased tax burden that would result from a influx of new Garnet Valley School District students, and infrastructure considerations such as sewer and surface drainage.

Meanwhile, the BVC commissioned almost a dozen consultants who are experts in their fields to perform studies in conjunction with Concord Township’s research. This was done in the interest of heading off the next round of the conflict; Save the Valley and the BVC both anticipated that the developers would return volley with a new scheme. The BVC’s consultants investigated the area’s traffic loads, relevant ecological matters, its historic aspects, the economic considerations, and other factors... all pieces important to the puzzle that shows why developing this land is simply a bad idea.

Back With Another Proposal

Despite being thwarted once, the developers returned with what’s called a “by-right” plan... although in reality it was not. A by-right plan involves what developers are allowed to build, under existing laws, on a given piece of property, by right of their ownership. But anything outside current building laws (zoning) is not a by-right matter at all.

For example, as the owner of the land on which your house sits, you are probably allowed to build a shed in your back yard, but you’re not allowed to build a power plant. It’s your right to build what you want on your property so long as it conforms to the zoning laws; a shed falls within in those zoning parameters but a power plant would not. Meanwhile, we need to be transparent and consider what “a by-right plan” actually means. Examining the details of the developers’ proposals made clear that they were attempting to work around the rules, because:

- Variances do not equal a by-right plan, nor should they factor into one.

- Incomplete plans do not constitute a by-right plan.

- A misleading proposal should not be mistaken for a by-right plan.

None of these things is found in a true by-right proposal. This means that the developers did not, in fact, put forth a by-right proposal at all: The plans were misleading, incomplete, required 10 variances, and had upward of 45 code violations! Plans can be rejected for just one of these elements, and this case shines much-needed light on what developers can and will do to realize their agenda. Their plan was, in reality, a rezoning proposal being stuffed into a by-right envelope. The developers were not complying with the existing laws of Concord Township at all; what they were doing was, in effect, the equivalent of submitting plans for a shed while building a power plant. This is important — not to mention deceptive — because the Concord Township Board of Supervisors and Planning Commission cannot reject a by-right proposal. They can, however, reject a proposal that’s not by-right.

Around this time, it became evident that the Township was not always playing by its own rules: Numerous meetings for the Township’s planning commission and board of supervisors were cancelled just before starting; scheduled for inconvenient times; or called at the last minute, which would allow the public as little time as possible to organize. Other meetings failed to provide opportunity for public comment, and some were held with no occasion for voting on the proceedings, which simply draws out the process and wears down opposition.

You can read more details about this on our Justice Served article.

A Battle Won... But the War is Not Over

After the plan for 171 homes was approved, Save the Valley and the BVC appealed the decision in court. Then, in October of 2016, Delaware County Court of Common Pleas Judge G. Michael Green blocked the development of Vineyard Commons and directed Concord Township’s Board of Supervisors to hold new hearings on the matter. Green stipulated that the Board is obligated to ensure that the proposal will agree with an amendment of the Pennsylvania Constitution that safeguards citizens’ “right to clean air, pure water, and to the preservation of the natural, scenic, historic and esthetic values of the environment.” It remains to be seen how the developers will respond. For the present, it appears that they’ve received a substantial reality-check.

Despite continued opposition from hundreds of residents of Concord Township and the surrounding communities, as well as the expert testimony from the BVC’s consultants, the Board of Supervisors approved, in March of 2015, the plan to build 171 houses with the stipulation that a few of the requested variances not be granted. Slight plan modifications to accommodate that brought the number of houses down to 160. BVC successfully appealed the township’s decision to approve the plan at all. This means that any new plans, moving forward, would have to adhere to more challenging regulations as well as comply with the BVC’s newly adopted township code improvements. Having to comply with all of this has left the development not worth doing. What is significant here is that building on this smaller scale would not allow the developers to realize the profits they’d first envisioned... which gave them even less incentive to proceed. Meanwhile, the surrounding community was not 100% on board with any development on that parcel of land to begin with. And the land in question is presently owned by Woodlawn and slated for development by McKee Concord Homes LP and Eastern States Development Co., Inc. — the latter of which has deep ties to Woodlawn. Thus, the interconnectedness and interests of all these parties is not difficult to recognize.

A Loss Elsewhere

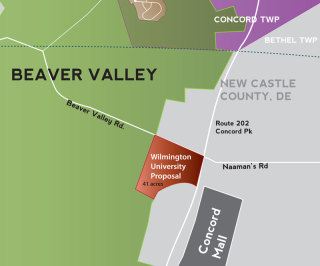

Meanwhile, resistance to another current flashpoint, the expansion of Wilmington University, has gone less well. As of July 2016, the New Castle County Council approved a waiver exempting the expansion’s developers from conforming with existing traffic regulations. This has not happened often, but apparently has a history along parts of Route 202 within Delaware. Essentially, it comes down to the school having secured permission to proceed with constructing three new three-story buildings on the 41-acre site where Routes 202 and 92 meet... simply by agreeing to “take steps to lessen its traffic impact” during morning and evening rush hours.

Normally, once it’s determined that new development will nudge traffic congestion past agreed-upon acceptable levels, the developer is required to cover the cost of the accommodating road improvements. Part of the County’s rationale for the waiver here was the general understanding that using that parcel for more retail and hospitality space — as had been sought originally by various parties over many years — would be a scenario much worse.

One potential bright spot is that of those 41 acres, only 12 will be developed by the University; 29 will remain open. Still, that the First State National Historic Park is nearby, and that wholly unprotected land lies between it and the University’s expansion site, is ample cause for concern over future development and we are wary of the precedent being set.

What Comes Next?

Our successful appeal of Concord Township’s original approval for a scaled-down Vineyard Commons, and Judge Green’s decision to force its developers to tailor their plans, demonstrates clearly the power that the people have — if it’s organized and channeled the right way. Still, this was one small victory against very powerful, very established institutions.

It’s not merely that more development in The Valley is a discernible negative — considering nothing but the increased congestion, traffic, and air and water pollution that will result — but also that leaving this pristine land alone is a discernible positive. There are very few issues or problems that have ideal solutions; frequently the best outcome will be one of simple balance.

And given that Beaver Valley is so close to rampant growth and sprawl that shows no recognizable signs of slowing, it is our contention that the larger, surrounding area is already as out of balance as should be allowed. More is not necessarily always better.

Please join us and support our efforts in any way that you can. The forces we oppose are quite substantial and are not lacking for resources to support their plans. It is unlikely that they will rest... thus it is imperative that we do not, either.

Save The Valley

All rights reserved

Website made by Trolley Web